Resource

Grieving the Ideal

As a therapist who specializes in both grief and complex trauma, I often need to let clients know something up front: if we’re ready to process trauma, we’re going to do some grieving.

Many survivors may not be aware that grief is a common — if not inevitable — part of healing from sexual violence. If you’ve survived sexual trauma, one of the most fundamental aspects of your selfhood — your sexuality — has been wounded. The trauma piece is self-evident. But with that violation comes a grief you may not have anticipated. Healing from trauma, in whichever way works best for you, can help to alleviate pain and distress, allowing us to feel more safe in our bodies and even with others who are worthy of trust. But grief remains, and with it, some of life’s more challenging questions: How do I see myself now? How do I grieve the person I was while recognizing I’ll never be quite the same? How do I find acceptance?

Trauma and Grief Go Hand-in-Hand

I like to say that not all grief work is trauma work, but all trauma work will involve grief work. I also find it important to note that, while related, these two processes are different and tend to run on separate timelines.

Let’s start by setting some expectations. Trauma, or at least our response to it, is something we can confront and heal. You can seek a number of treatments for post-traumatic stress and these will work specifically to help you feel better. Grief, on the other hand, has no cure. It’s something that will always take up some space in our lives.

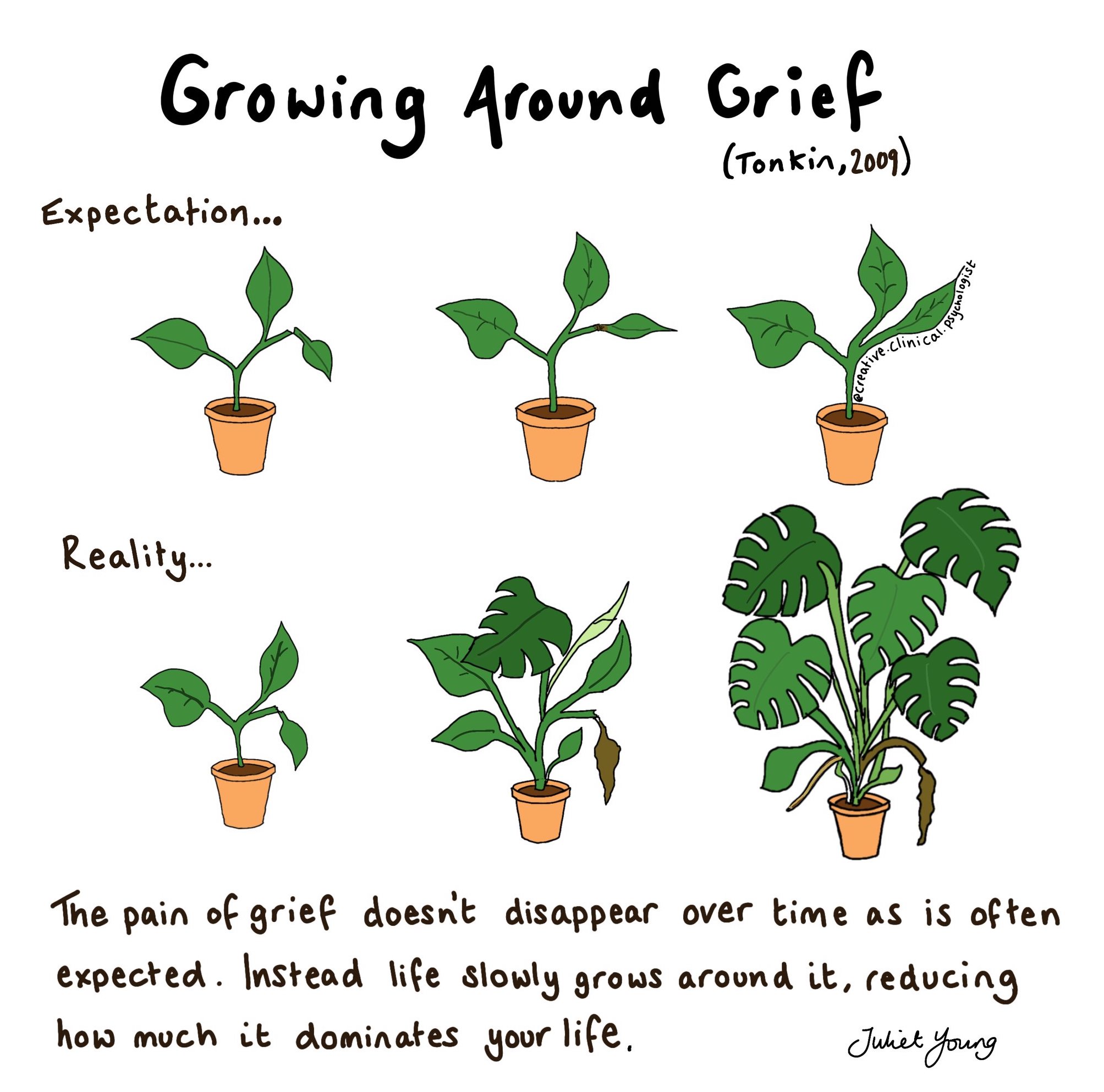

Grief shows up in those moments when we look for someone or something—even an aspect of ourselves—and find that it’s no longer there. These moments can be so destabilizing and painful at first, but they grow more familiar. The absence doesn’t go away, but we get used to it. According to Dr. Lois Tonkin’s model of grief, we learn to learn to grow and change around it.

Allow this infographic to illustrate:

Illustration from X post by Juliet Young, Clinical Psychologist

After experiencing sexual violence, many survivors may carry feelings of hopelessness and deep loss, but that doesn’t mean we stop growing. The truth is that we can learn to carry and honor the wait of the experience, and continue to grow around it.

Processing Grief After Trauma

We’ve spent some time on how grief shows up in the aftermath of sexual violence, but it’s time to bring trauma back into the conversation. Again, while related, trauma and grief are two separate processes that deserve respective attention. Let’s turn to the great Judith Herman for a definition of trauma:

“Psychological trauma is an affiliation of the powerless. At the moment of trauma, the victim is rendered helpless by overwhelming force. Traumatic events overwhelm the ordinary systems of care that give people a sense of control, connection, and meaning.

Traumatic events…overwhelm the ordinary human adaptations to life. Unlike commonplace misfortunes, traumatic events generally involve threats to life or bodily integrity, or a close personal encounter with violence and death. They confront human beings with the extremities of helplessness and terror, and evoke the responses of catastrophe.” (from Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, by Judith Lewis Herman MD)

When traumatic events happen, they overwhelm and disrupt the way we see ourselves and others. What’s left in the wake of trauma is grief. Here, we can see how trauma and grief often go hand-in-hand. We reach for our former self and they’re not there. We look for security in another person and can’t find it. That’s grief.

If you experienced sexual trauma in childhood, you may need to grieve the childhood you never got to experience. This is where inner child work becomes so critical. Oftentimes, I’ll help clients revisit the time at which they experienced a trauma and subsequent loss in order to recover that piece of self, to reconnect with and reclaim it.

One way of grieving our lost childhood and healing the inner child is to reflect on what we missed out on as kids, and then quite literally give that to ourselves. For many survivors, there is the feeling of having grown up too fast. Being sexualized at a young age, you may never have gotten the chance to experience true playfulness, openness, innocence or silliness—all fundamental aspects of childhood.

To reconnect with that child who got left behind, think of what they wanted but didn’t get to have back then. Was it a certain toy? A trip somewhere? Or simply someone to talk to? However possible, seek out those experiences that may be more available to you now, as an adult, than when you wanted them as a child. This can help you reconnect with the kid you didn’t get to be and create a new sense of wholeness.

I’ve referred mainly to sexual violence that occurs during childhood so far, but such trauma can occur at any age and can be just as wounding, no matter when it happens in a person’s lifetime. For those of us who have experienced this kind of violence later in life, the chapters in which the trauma occurred can feel erased, muddled or closed off. It can feel like that time was stolen from us. Similarly to with inner child work, it can be helpful to identify the parts of our lives that were impacted by trauma and reclaim them. For instance, if you experienced assault in college, that environment and all of its associations (learning, young adulthood, early aspirations) may have been tainted by the event. It can be helpful to take time to honor what was lost—to acknowledge the value it had for you then, to parse out what might be reclaimed today, and to let go of what’s gone.

Part of the task of survivorship is learning, as Ayesha Sidiqqi put it, to “Be the person you needed as a child.” The first step to this process is to acknowledge and grieve what you didn’t have. Sometimes, clients and I will do something called childhood rescripting, where we revisit a painful memory, acknowledge what they needed and didn’t get at that time (support, comfort, validation), and then reimagine the scene playing out with either their adult self, myself or another trusted adult stepping in to provide what was missing. A number of clients have reported to me that they told a parent about their abuse and the parent didn’t do anything. When rescripting that memory, I might ask a client to imagine themselves as an adult stepping in, validating their younger self and even seeking justice for that young survivor.

Everyone’s Path is Unique

You may have heard the cliché that healing is nonlinear. That’s true, but allow me a linear analogy to illustrate this kind of loss:

Think of life like floating down a river. When we experience something as traumatic as sexual abuse, it’s like dropping a piece of ourselves in the river. We might not even realize it’s missing until much further down the line, and by that point, we’re left heartbroken by the realization that it’s gone. We can’t go back and retrieve it. We certainly can’t change the course of the river. But we can grieve what was lost and learn to adapt to the rest of the ride.

One of the most important facets of recovery is grieving the ideal: the ideal life, the ideal parent, the ideal family. We all want what’s best for ourselves and we all want the people in our lives to be reliable and trustworthy. When sexual abuse occurs, that trust gets shattered. Survivors who were abused by a person they once trusted may struggle to look at others - not just perpetrators, but oftentimes people in general - the same way. It’s normal to feel frustrated, demoralized or even infuriated in the wake of sexual violence. Such events can change everything, and it is okay to grieve the huge shifts in mindset and lived experience that follow.

There’s no way around grief. We can only go through it. And while the Five Stages of Grief have long been debunked as a predictable process, we will likely endure our fair share of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance as we move through the process.

I can’t overstate how important it is to find support while grieving. So much of what makes a memory re-traumatizing is a lack of safety and security in its aftermath. Simply being invalidated by someone when telling them what happened can have a seriously damaging impact (Hong & Lishner, 2015). But by that same token, to find support and compassion around trauma can be deeply healing. For many people, some form of faith is helpful to find meaning and acceptance. For others, that very suggestion is offensive at best. There is no right or wrong way for everyone to grieve, but there is a way that works for you. The important thing is to find someone—be it a therapist, a trusted friend or relative, or a support group—who can support you as you navigate your own individual path to healing.